Festivities planned for the 100th anniversary of Richard Nixon's carefully preserved birthplace in Yorba Linda remind me of the time he accused me of having a secret plan to ensconce his library in a red light district.

Festivities planned for the 100th anniversary of Richard Nixon's carefully preserved birthplace in Yorba Linda remind me of the time he accused me of having a secret plan to ensconce his library in a red light district.When it opened on a red-hot day in July 1990, the Nixon library was an immaculately landscaped inferiority complex, a presidential library in shiny new nameplate only. It wouldn’t deserve the title for another 17 years, when it became part of the National Archives and took possession of tens of millions of White House documents, tapes, photos, videos, and gifts.

Nixon had nothing against having the records in his library, though he could've done without most of the professors who'd be pawing through them. But by the time his friends had contributed $24 million and we were ready to break ground, his struggle with the National Archives seemed interminable, thanks in large part to his own post-Watergate maneuvers. His lawyers and I, as his chief aide, were working hard to make sure that his infamous tapes weren’t opened to the public unless his conditions about purely private segments and documents were met. He’d also brought a suit of his own demanding to be compensated for the seizure of his records by Congress after his resignation in 1974.

In the early 1980s, the feds, indulging in some wishful thinking, had gone through the motions of drawing up plans for a governmental Nixonland that was to have been perched on a bluff with a magnificent Pacific Ocean view in San Clemente, where the Nixons had lived from 1969, the beginning of his presidency, until 1980, when they moved to New York. When the project was stalled by local land-use politics, we pulled the plug. If the San Clemente library had gotten any further along in the planning and budget process, Congress would probably have demanded that Nixon settle his differences with the federal government before expecting it to spend millions each year to operate his library. (After his death, I got the job of settling them.)

Nixon shed no tears as he again waved goodbye to San Clemente. He’d always wanted to build in the north Orange County town where he’d been born in 1913

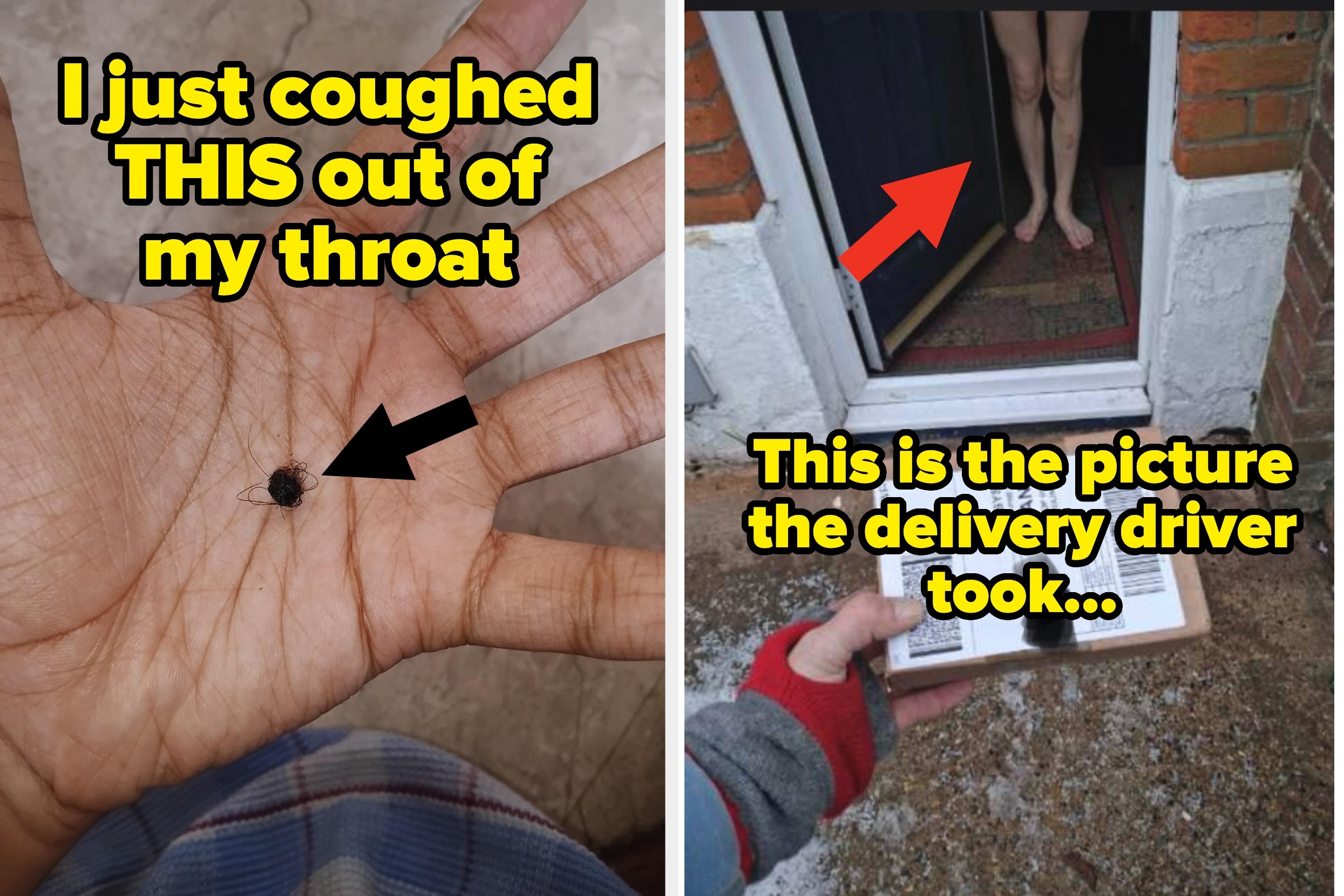

, and he finally saw his opportunity. By now, there was no talk of the National Archives running the library. In 1986, he sent me to Yorba Linda to make sure the city would do everything possible to help our private foundation make a go on our own. On the way I collected Bob Finch (shown above) and Maury Stans, Nixon’s political buddies and cabinet members, who were helping raise money for the library. They were disappointed by our decision to abandon San Clemente, and I was hoping to sell them on Nixon's Yorba Linda dream.

, and he finally saw his opportunity. By now, there was no talk of the National Archives running the library. In 1986, he sent me to Yorba Linda to make sure the city would do everything possible to help our private foundation make a go on our own. On the way I collected Bob Finch (shown above) and Maury Stans, Nixon’s political buddies and cabinet members, who were helping raise money for the library. They were disappointed by our decision to abandon San Clemente, and I was hoping to sell them on Nixon's Yorba Linda dream.We arrived late on a cloudy morning. My companions were denizens of old Pasadena, corporate Republicans of the old school, resplendent in crisp blue pinstripe. Both are gone. If they weren't, on today's political scale they'd show up to the left of Barack Obama, especially Finch, a gracious humanitarian and legendary party moderate. That day, they stood awkwardly on the gravel in front of the careworn Nixon house, sniffed the middle-class suburban air, and narrowly eyed the little bungalow's spotty green paint and the escrow office, day care center, and droopy power lines along Yorba Linda Boulevard.

I hoped their expressions would lighten when they saw the Nixon family’s historic home. Welcomed inside by the then-occupants, the caretaker of a nearby school and his family, Finch and Stans squeezed up through a narrow stairway to the tiny bedroom Richard had shared, as World War I raged, with his brothers Harold, Donald, and Arthur. A teenager had tacked a Van Halen poster to the slo

ping ceiling. It was a seminal seventies rock and roll band, I explained to the grey-haired eminences, adding what proved to be an unimpressive invocation of home town solidarity: “They’re from Pasadena.”

ping ceiling. It was a seminal seventies rock and roll band, I explained to the grey-haired eminences, adding what proved to be an unimpressive invocation of home town solidarity: “They’re from Pasadena.”The three of us were huddled together with bowed, bent heads, since the Nixon boys’ musty room offered about five and a half feet of vertical clearance. “Well, if it’s what Nixon really wants,” Stans said sulkily, staring at me sideways. The same day, the Yorba Linda city manager, Art Simonian (now Kathy's and my neighbor), told me he’d do whatever was necessary to get the library, including donating $1.3 million worth of land.

Returning to New York, I went to Nixon’s office to give him the good news only to have him ask me sternly and with not so much as a how-de-do why I was proposing to build his presidential library "right across the street from a massage parlor." This lurid picture had been painted by Pat Nixon's best friend, Helene Drown. Also an advocate of a more upscale site, Drown had been briefed by the pinstriped delegation from Orange Grove Boulevard and had then figured out ho

w to get the word to 37.

w to get the word to 37.Nixon was teasing me and also giving me a little whiff of how backhanded politics could be, even though the stakes had diminished to choosing the pasture where old politicians would graze. I laughed and explained that the establishment she, Stans, and Finch found offensive was a fitness center (currently the 24-Hour variety), which was housed in a rehabilitated citrus packing plant that might once have processed the lemons and oranges his father, Frank, had grown. Crisis averted, Nixon got his wish. To Yorba Linda he returned.

No comments:

Post a Comment